The deeds of cruelty, massacre, violence, pillage, arson, imprisoning prelates, burning down monasteries, robbing and killing monks and nuns and yet other outrages without number which he committed against our people, sparing neither age nor sex, religion nor rank, no-one could describe nor fully imagine unless he had seen them with his own eyes.

But from these countless evils we have been set free, by the help of Him who though He afflicts yet heals and restores, by our most tireless prince, King and lord, the lord Robert. He, that his people and his heritage might be delivered out of the hands of our enemies, bore cheerfully toil and fatigue, hunger and peril, like another Maccabaeus or Joshua. Him, too, divine providence, the succession to his right according to our laws and customs which we shall maintain to the death, and the due consent and assent of us all have made our prince and king. To him, as to the man by whom salvation has been wrought unto our people, we are bound both by his right and by his merits that our freedom may be still maintained, and by him, come what may, we mean to stand.

Yet if he should give up what he has begun, seeking to make us or our kingdom subject to the King of England or the English, we should exert ourselves at once to drive him out as our enemy and a subverter of his own right and ours, and make some other man who was well able to defend us our King; for, as long as a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be subjected to the lordship of the English. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.

– Declaration of Arbroath

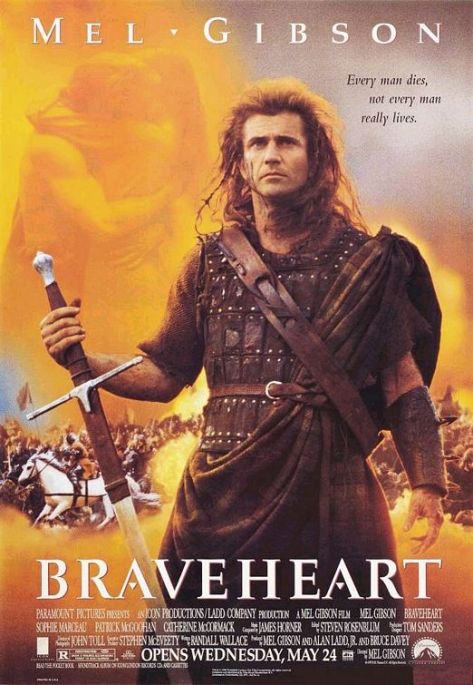

Braveheart is a film which I believe will become important in the history of Scotland. I’m extremely… ambivalent about Mel Gibson’s work, in that I both love it and hate it for several reasons. Yes, I know, it’s “Hollywood not History,” you can’t expect complete fidelity to current understanding of historical events, there are going to be changes for the benefit of modern audiences, et cetera. It’s become something of a potent symbol of the independence cause in Scotland – but strangely, a symbol applied by its critics more often than its supporters. Usually this takes the form of patronising articles that suppose modern independence supporters cannot tell the difference between Medieval and modern politics, that they’re over-emotional softies who let their hearts rule their heads, and that they’ve fallen prey to a Hollywood fantasy version of Medieval Scotland.

For my part, I think Braveheart was about more than Scottish Independence, or about the events of that war, or Wallace himself: it was about the forging and consolidation of national identity.

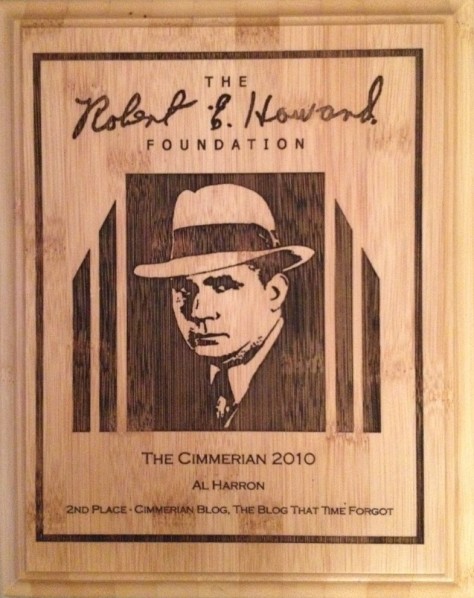

As so frequently occurs, my time in the Robert E. Howard community has been deeply educational for me in other walks of life.

There’s a certain power when you have knowledge over an esoteric subject. You feel special, in control, respected, important: that you are an oracle to whom those without knowledge or direction come, a scholar whose expertise will set you right – an attendant at the fountain of knowledge with a quaich for thirsty travellers at the ready. That sense of importance can be very seductive: easily warped from a place of genuine desire to impart knowledge, into a bludgeon with which to bully those without your vast experience. It’s easy to cross that fine line from ambassador to gatekeeper. I had to battle such unconscious sensations as I accumulated more and more knowledge of Robert E. Howard. Sometimes I let it get to my head despite my raging Imposter Syndrome – neither contradictory problem helped when I actually won an award for my work. As I saw more and more disinformation and outright falsehoods about an author whose work I adored appearing all the time – well, when you have a hammer, all you see are skulls to smite?

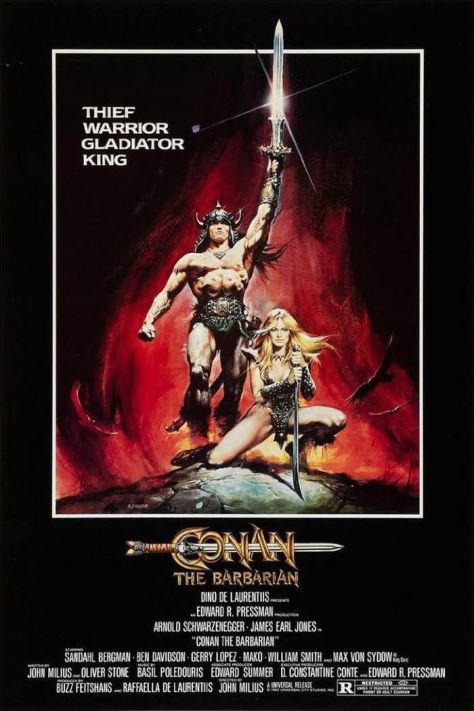

See, the Robert E. Howard community has its own Braveheart to deal with: 1982’s Conan the Barbarian. Conan, the character, had been around for 50 years before the film’s premiere: he was already the star of bestselling novels and one of the hottest Marvel Comics of the Bronze Age. But something strange started to happen over the next few decades: Conan, who was the star of comics, cartoons, and TV series all the way to the end of the 20th Century, started to be equated more and more with the 1982 film than the decades of fiction that preceded it. It got to the point where any mention of Conan in popular culture would evoke not Howard’s original creation, nor the visual renderings by Barry Smith or John Buscema, but the Austrian Oak.

This wouldn’t have been so bad if Conan the Barbarian wasn’t an inversion of the original character in too many ways to count. Nearly everything – his appearance, his upbringing, his career, his personality, his personal history, his accent, the very pronunciation of his name – is completely and utterly different from everything in the original source.

For a while, every time I saw Someone Being Wrong On The Internet about Robert E. Howard & Conan, I felt the need to interject like some sort of Church of Latter Day REH evangelist. No internet video reviewer, no random blog post, no newspaper op-ed was safe. “The Wheel of Pain never actually existed.” “That whole thing about Conan’s parents being murdered & his village being destroyed never happened.” “Conan was never sold into slavery as a child.” “Conan never met Thulsa Doom in the first place, & couldn’t because the timeline was completely out of joint.” “The clothing of the Hyborian Kingdoms was completely different in that period.” “Conan didn’t wear warpaint like a Pict.”

Despite appearances, it wasn’t about proving myself in some sort of weird nerd-one-upmanship (a Pyrrhic Victory if ever there was one) – it was because I loved REH and his work, and wanted to share the real Conan (insofar as there can be a “real” Conan) whenever there was an opportunity, because I thought Howard’s work had a lot more to it than people gave it credit for. But that sense of intellectual power can be very persuasive, and constant vigilance is needed to stop yourself from being that guy.

So it can be with Braveheart. I’m sure many Scots feel a certain sense of satisfaction in pointing out its inaccuracies. “Jus Primae Noctis never actually existed.” “That whole thing about Wallace’s family being murdered & his village being destroyed never happened.” “Wallace was never forced out of Scotland as a child.” “Wallace never met Isabella of France in the first place, & couldn’t because the timeline is completely out of joint.” “The clothing of the Scots was completely different in that period.” “Wallace didn’t wear warpaint like a Pict.” “There was a bridge at the Battle of Stirling Bridge.” I can hear it. I’ve often said it. And it gets tiresome when the very first thing you hear with any discussion of Braveheart is how inaccurate it is, as if this is some shocking new information that’s never come up in the 23 years since its release.

Something happened after years of denouncing the crimes of Conan the Barbarian and Braveheart to anyone who would listen or was too slow to escape from earshot – I started to look at them not as failures to respect their sources, but as interpretations of those sources. Fidelity is not mandatory when it comes to adaptation (unless you’re going to proudly proclaim your work to be supremely accurate and end up being the opposite, in which case enjoy your petard), and this applies to history as much as it does 1930s fictional characters. Conan the Barbarian was John Milius’ interpretation of Robert E. Howard’s original stories: likewise, Braveheart was Mel Gibson’s interpretation of Randall Wallace’s script, itself based on Blind Harry.

From that perspective, I started to reappraise the “inaccuracies” of the film. I don’t think it’s a mistake that the Scots as depicted are a melange of several periods in history – one could argue that they represent all Scots across time. Blue warpaint and Iron Age architecture from the Picts and Antiquity; kilts and tartan from the Gaels and the Middle Ages; the Scots language and vernacular from the Lowlands and Early Modern times; all mixed together with the Scottish romanticism of Walter Scott and James MacPherson alongside the mythmaking of Blind Harry, Thomas the Rhymer, and John Barbour. After the rocky start of Alba, this was the first time Scotland was truly united, that the descendants of disparate tribes of Gaels, Britons, Norsemen, Picts and Normans decided that they were no longer separate peoples that happened to live in Scotland – they were all Scots. One could argue that this was more a result of Hollywood’s tendency to conflate and simplify for mass consumption, and in truth, that might well be the case – but in doing so, this simplification acted fortuitously as a distillation of Scots and Scotland’s national character.

There are many within the UK which love to downplay, ridicule or outright twist the events of that period. Braveheart itself was used as a vehicle for attacks on the very idea of commemorating Scottish history:

Bad history is potentially dangerous. In this case, ‘Braveheart’ can scarcely fail to feed the growing Anglophobia which is, to many Scotsmen, a pernicious feature of our country today. If it does so, it will be not only a bad film but a deplorable and damaging one.

– Allan MassieDo we need to reach back so far to find a mascot? This tribal symbolism, whatever it once meant, means nothing now. Legends are dangerous things. We can do better than Wallace, the man formerly not known as Braveheart.

– Ian BellIt is very much a Scotland versus England story. Freedom is equated with independence. Lots of insults are thrown at the English.

– Brian Prendreigh

And so as we approached the 700th anniversary of Bannockburn, evoked at the end of Braveheart, there was a significant tendency to downplay it. It’s “irrelevant to current Scotland,” it’s “ancient history,” it’s “Hollywood kitsch that bears no relation to reality.” John McTernan calls Bannockburn “the anniversary of some battle between Anglo-French noblemen about precisely which of them would have the right to steal Scottish lands and enslave ordinary people.” Ian Davidson said commemoration of June 24th was tantamount to celebrating “the murder of hundreds of thousands of English people.” Mark McLachlan seems to think the 100th anniversary of Ypres was more important than “something we only know about through bad movies and romantic novels” and “far more relevant to the Scottish electorate than long dead Kings” – as if there was some sort of Sliding Scale of Relevance in history based on distance.

And most tragically of all, many proud Scots bought into this, apologising for Braveheart and the enthusiastic response it instilled. “You’re right, it is a Hollywood fantasy, it is an illusion, a lie.” Never mind that Scottish Romanticism is a thoroughly Scottish invention which existed centuries before your Brigadoons and your Bravehearts; never mind that Braveheart remains one of only a handful of films that even attempts to present that period of Scotland’s history; never mind that the Scottish independence movement has survived far worse than a film’s reception. What sort of country apologises for a film which depicts their nation’s people repulsing an invading enemy that is intent on its cultural destruction, as depicted through the mythic lense of a Scottish minstrel?

I guess the same country which promotes the glory of the enemy army in the film: together, Scotland and England would be founders of the British Empire, a glorious and terrible institution with a legacy of unmatched majesty and profound shame. It’s a wicked game to play, to actively undermine a nation’s fight for freedom against an invading force on one hand, yet promote another nation’s imperial conquests and domination on the other. And even though Scotland is part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, “British” and “English” are often treated as synonymous: “Scottish” is all too often a term of distinction from “British,” from sources biased and neutral alike. And so the Industrial Revolution, the Enlightenment, and Romanticism as “British” can often be interpreted as “English” – despite the contributions of the Scots, Welsh and Irish. Of course, the reverse is also the case, where British atrocities like the Highland Clearances are falsely equated with the English – it was Scottish nobles, beneficiaries of privilege and the British establishment, who betrayed their people.

The Jubilee, the Olympics, and the centenary of the start of the First World War: celebrations of one vast, monolithic Britain, with precious little celebration of Wales, Ireland or Scotland despite the previously-indicated synonymity of Britain with England. The intent was to make the fatal mistake, to show the Union as a homogenous whole, not a fusion of four nations – and since the English population dominates, it’s natural that this monolithic Britain bears more resemblance to England than any of the other constituent nations. The history and legacy of those countries as individual nations is rendered irrelevant, illegitimate, beneath consideration compared to Mighty Blighty.

The way Scottish Twitter or Facebook talks, you’d think Braveheart was a joke. In other parts of the world, it’s an inspiration.

I have to be truthful here: From my experience of travelling the world in the immediate aftermath of the movie – and still to some extent – when you say you’re Scottish, the first reaction is: “Ah, Braveheart.” And a big grin. The embarrassing aspect of this is that people think too highly of us. Certainly since Braveheart, they’ve had this belief that the Scots are brave. Having said that, john and I ran a website about the movie, so we got emails from around the world. We even got emails from Iraqis who said they were watching Braveheart in bunkers as bombs fell. Their message was that they needed to get a sense of the small guy succeeding, however daunting the odds.

– Lin AndersonThe Kosovars reportedly watched Braveheart many times, recognizing it as “our story too.”

– Frances Trix, Albanians in MichiganDuring a screening of the 1995 film Braveheart in a Pristina cinema, the excitement of youth for the new generation of resistance heroes was so palpable that the Serbian police had to intervene to stop them chanting ‘Kosovo Republic’ in the cinema.

– Roger Boyes & Suzy Jagger, New State, Modern Statesman: Hashim Thaçi – A BiographyThe bird arrived ten minutes later. I felt like William Wallace in the movie Braveheart, when he triumphantly yells out “Freeeeedom” just before his execution. I boarded the CH-53 Super Stallion helicopter and screamed William Wallace’s final word, inaudible to anyone else because of the helicopter’s engine noise. I was finally free.

– Wesley R. Gray, Embedded: A Marine Corps Adviser Inside the Iraqi ArmyIndeed, the Scottish clans are frequently compared with other thistle-like tribes such as the Pukhtun, Somali, Kurd, and Bedouin… More recently, Kurds holding training exercises in the hills and caves of Qandil in northern Iraq have tried to inspire recruits with showings of Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, a film about William Wallace, the legendary Scottish freedom fighter. In the film’s final scene, Wallace is tortured to death but refuses to compromise, instead shouting with his last breath the one word tribesmen everywhere find closest to their hearts – “Freedom!”

Love of freedom, egalitarianism, a tribal lineage system defined by common ancestors and clans, a martial tradition, and a highly developed code of honor and revenge – these are the thistle-like characteristics of the tribal societies under discussion here.

– Akbar Ahmed, The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became A Global War on Tribal Islam‘Braveheart‘ was our favorite movie, and we watched it at least once every couple of days. One Chechen fighter who had lost his arms would always jump up and demonstrate to all of us how he would swing a sword like Mel Gibson if he still had arms. ‘Look, I’m so fast you can’t see my hands,’ he would say as he swung his stumps around.”

– Aukai Collins, An American Fighter’s War in Chechnya

That Braveheart can speak so powerfully to such a wide range of movements in such different environments and political situations suggests there is something more to it than its detractors suggest.

The modern mythology of Scotland, even Brigadoon and Whisky Galore and Trainspotting, is a reflection of the nation’s character. Braveheart is still part of us – and it will be for as long as we don’t have control over our own media. It is Scotland’s favourite Scottish film by a significant margin, no matter how much some of us in the independence movement may cringe at its very mention. It remains one of only a few theatrical films which documents one of the most important periods of Scotland’s 1000-year-plus history – not least because Scotland does not have its own film industry to speak of. How on earth are we supposed to break free of the Braveheart caricature when Braveheart is practically all we have for that entire period of our history?

We’re getting there. Outlaw King is on the horizon, as is Robert the Bruce, and no doubt more to follow. The day will come when the people of Scotland can tell our own stories unfettered by regionalist myopia of our larger neighbours, or international mythologising of well-meaning outside voices. And then we can affect the world – and ourselves – as strongly and surely as Braveheart has already.

After a long walk and a wait, a lorry came along and I was offered a lift. But The Lads had a last urgent question. One of them came forward as spokesman.

“Answer me: true or false,” he said. “Is the movie Braveheart true history?”

I was taken aback. “You watch films?” “There’s a generator, and we watch on Sundays. What about Braveheart?”

I pondered. “Yes, I think the story is basically true.”

They all sighed with evident satisfaction. “We love that movie,” said another. “We cry a lot.”

– Kevin Rushby and the people of Namasaro, Papua New Guinea: A trek to the village time forgot

I offer you a way to be a Braveheart exactly like William Wallace, who lives forever in the minds and hearts of all of us who would put ourselves between the problem and the people we care for, even to death, but not today through fighting each other. I feel so connected with all of the Sparticus stand-ups the world over, and its time for The Divine Spark in all of us to lay down our swords and shields and pour the effort into really fighting, with Love for Peace and an end to suffering and hunger, if one is in pain we are all suffering. Spend all the money and all the effort on good stuff instead, Bairns Not Bombs. The Peace exists and we disturb it, against the Law. We are being harnessed under the wrong leaders. Our leaders should be the Peacemakers and positive people with hope, the Storytellers and the artists. This is the message of Braveheart for me, all of us are one. International Day of Peace is on 21st of September and on 22nd there is a visit to Faslane in Scotland where Trident exists. Everywhere there are events for Peace. We are all united, blue in the face and we can only gently oppose with light in the darkness, in numbers, because we are seeking Peace. Sign the Fuji Declaration of Peace and have Peace in your heart. May Peace Prevail On Earth. https://fujideclaration.org/the-fuji-declaration/

One inaccuracy of your of your own, there were no Normans in the Kingdom of Alba, the timeline is all wrong. Alba came out of a common enemy, not England but Northumbria whose demesne once stretched to the Lothians.

The Picts beat them at Dun Nechtan and killed their king and then joined the Scotti and the Strathclyde Britons, not sure there were any Norse on the Alba side initially either come to that. They came later with that dowry and bringing the Kingdom of the Isles in line.

The Normans didn’t come until David I invited them in and introduced feudalism to the lowlands. An improvement to the clannism but we were stuck with it until the very end of last century.

The Vikings who became the Normans might well have been ravaging and settling Northern France around the time of Alba but they hadn’t become Normans yet. England was still a patchwork of warring kingdoms, the line of the Danelaw still mattered. My father’s family come from smack bang on the Danish side but right on the line. Our surname is obviously of Danish origin, ending in ‘by’.

Ah, I think I might’ve been unclear: I was specifically referring to the time of Wallace as the first time Scotland was united culturally & politically, not the formation of Alba itself. The kingdoms of Moray, Strathclyde, Northumbria, and others were still around at the time of Alba’s formation, and even after they became part of Scotland, there was still a residual sense of distinction among them. By Wallace’s time, those strands wove together, and people started to see themselves as Scots.

By far the best, well balanced Article I have read on Braveheart.

The Tale of the Lorry crew is Touching..As are the Quotes from around the world. I was at Bannockburn with the AUOB March / Rally very impressive area around the Bruce Monument.

Fair enjoyed the video of the Doom metal band Cheers

Interesting Comments too..From Geraldine, whom I have Met,

and Muscleguy.. Who pops up at Craig Murry Blog From time to time

[…] elements of the Yes movement do their best (yet again) to foment some sort of civil war over a popular 1990s movie for no better reason than to draw a little bit of attention to themselves in the face of […]

Al, I’ve been reading your blog for over 4 years & I think you are one of the very best & thoughtful writers in Scotland right now. But this article is the first to bring a tear to my eye. Just a wee one, mind.

I remember going to watch Braveheart with my (then) new girlfriend (now wife) in the cinema in Glasgow. It was her second time (she had a crush on Mel Gibson) & my first. I enjoyed it a lot, being a Wallace & having grown to with a belief in Independence & the part The Wallace had played in that story, but I was also a bit scathing about its cultural & historical accuracy. I do have to admit to owning a copy of the film on vhs, though I haven’t watched it in nearly 20 years.

During 2014 I was definitely not in favour of endorsing Braveheartism as a reason for Scottish independence & I am still not. But, the articles I’ve read (by various bloggers) in recent days, culminating in this one, makes me realise that I am more a victim of the Scottish cringe than I had realised. Educated Scots like me are forever pointing out how parochial or inaccurate or silly fictional accounts of historic Scotland are to show our English (sorry, I mean British) peers that we are not ignorant savages like our (unwashed) fellow countrymen & women who rapture in their enjoyment of base entertainment such as Braveheart. Oh no, we are far superior to those sorts of Scots. The fact that the story of Wallace, as depicted by an Australian actor in an American film made with large numbers of Irish extras, can inspire peoples around the world who are struggling for their freedom makes me realise I need to get off the high horse I didn’t realise I was riding & embrace the spirit of Braveheart.

Braveheart will be being played (on vhs) in this household this weekend.

Nobody else seems bothered when history is hackneyed by Hollywood. Just Scots. In fact no-one cares about other hackneyed Scottish films. Just Braveheart. It is because such a large part of the Scottish psyche is given over to worrying about what the English think.

Ironically that concern over the impression we make may have one positive aspect. You could argue it is a driver for the lack of racism and ethnic exceptionalism in the independence movement. If we didn’t care what the English thought of us, would we be as racist as their Brexiteers?

Braveheart rips that worry right off and gets you in the gut. The English aren’t used to being portayed as the baddies and they hate it. The people who worry about what the English think hate it. People – anyone round the world – fighting an independence movement love it.

The historical accuracy of Braveheart is completely irrelevant. What is relevant is its emotional potency. That’s what people are really trying to target and belittle. If like Brexit, it gives people the green light to vent racist thoughts against the English then obviously that is unacceptable. But there is no doubt it stirs some kind of emotion. I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that myself.

As thoughtful and thought provoking as always Al.

Well put. I’ve always thought of and revered Wallace as more of an amalgamation of all who fought for Scotland’s existence, than for the singular champion he was. A figurehead of sorts, that represents the struggle, will, and heart of a nation in both history, and modern pop culture.